25 March 2017

“India is opium” declares Rishi as we hurtle through the streets – mostly on the wrong side of the road – and I am finding it increasingly hard to disagree. I have travelled to Jodhpur, home of Rajasthan’s most impressive citadel Meherangar Fort, described by Rudyard Kipling as the “work of giants”. Here Rishi, tuk tuk driver and self-appointed tour guide, has declared me a “nice person” and taken me under his wing for the day. I am sure he adopts a similar tack with all potential customers, but I have vowed to suspend cynicism for the duration of this trip and am taking all friendly gestures at face value. Besides which, he proves an entertaining companion as we career towards the colossal edifice which towers over the town. As well as attracting tourists because of the fort, Rishi tells me, Jodhpur is also a renowned centre for spices. “You Britishers” he chortles, scattering pedestrians in his wake “You love to buy the spices, but you have no idea what to do with them!” I smile weakly, forbearing to mention the prevalence of curry powder in UK kitchens – total anathema – indeed fiction – to all Indian cooks. Our national failings have however, provided enterprising Rishi with a business opportunity: he and his wife run Indian cookery classes from their little house in the Old Town. “We have just been awarded five stars on the Trip Advisor!” he declares excitedly as we screech to a halt at the perpendicular fort entrance. Here I am deposited with a promise that he will be waiting when I emerge (which he is, two hours later) for onward conveyance to the next stop.

I heave myself up to the ticket office. It is not yet ten o’clock but already it is over 30 degrees and rising. Meherangar Fort offers visitors an audio guide, a welcome innovation because it deters the hawkers who hang about at all sight entrances in India offering – with varying degrees of aggression and differing price points, to show you around. But to obtain the audio guide, you must leave a deposit of passport, credit card or 2000 rupees (about £25). Although past experience, and the assiduous docketing I can see going on behind the counter, reassure me that relinquished property will eventually be restored to its owner when the time is right, I am reluctant to part with any of the prescribed items and survey my purse for alternative forms of ID. Pondering which of its contents I could afford to manage without should the worst come to the worst, the answer to my dilemma becomes rapidly obvious and my European Health Insurance Card is shortly being deemed an acceptable hostage by the ticket seller, although he scrutinises it sceptically for a while, probably well aware he has been hoodwinked.

The guide proves a sound investment: it navigates me effortlessly round the fort, and is a source of amusement to boot, since Laurence Olivier appears to have been resurrected to voice the English version, and the narrative contains some quaint usages of the language. I am frequently asked to “proceed forthwith” while “miscreants” and “rogues” feature prominently. There are some incredible exhibits in the fort museum including a display of vintage howdahs and palanquins – better known as elephant seats and litters. The elaborate gilded palanquin in the picture below was seized in battle from the Mughal leader of Gujarat, is plate glass, took 12 men to hoist it aloft and contains a full size double bed for the occupant (s).

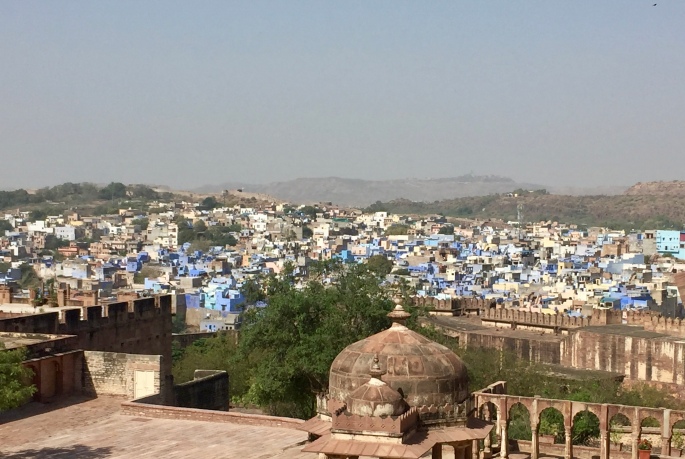

The elevation of the fort allows for splendid views of the city below, especially Jodhpur’s famous blue houses which nestle beneath the walls in a scene commonly likened to a Cubist painting. Blue is the colour of Brahmins, and the indigo wash used on the buildings is also said to have mosquito repelling properties. I am trying to educate myself about the caste system while I am here because it still has such an enduring impact on social and economic position in India. “Caste” is actually an English construction which conflates the “varna” system of four Hindu social groupings (Brahmins – teachers and priests – are at the top of the tree) – with the “jat” system which essentially denotes the “clan” to which individuals belong and is more predictive of individual futures than caste. Marrying outside your “jat” is still frowned upon which seriously reduces social mobility, particularly in rural areas.

There have been many attempts at reforming the caste system over the centuries – Gandhi famously championed the cause of the “untouchables” (now an outlawed term) who fall outside and beneath the main varnas altogether. Today, discrimination on the basis of caste is illegal and a number of “jats” are subject to positive discrimination and certain quotas for public sector positions. Despite these advances, the system remains so indivisible from Hindu spiritual beliefs, whereby family of birth is an indication of “karma” ie a judgement on your conduct in previous lives, that breaking the paradigm completely feels a remote possibility. But as with so many other things, the philosophical approach of your average Indian puts everything in perspective. I leave the last word to Rishi, with whom I discuss all these issues on our journey home. “Brahmins no drink or smoke” he explains “and they eat no chilli or garlic. It would be so boring to be a Brahmin!”

Footnote: I am beginning to wilt in the heat. On arrival at the end of February, the weather was akin to a lovely English summer, and it even rained en route between Delhi and Agra. Now, the thermometer advances upwards on a daily basis: today it is 36 degrees with 41 promised next week and the sun’s rays have a searing, relentless quality here that I have experienced nowhere else. The weather app on my phone resolutely displays London and when I see “12: partly cloudy”, I begin to feel a little nostalgic, although the mere thought that I should at any time ever, have chosen to wear a puffa coat or a jumper, now makes me feel at risk of internal combustion. So I am highly receptive to all cooling strategies, and the most curious one I have yet heard is that I should carry an onion in my pocket: I am told the onion will then absorb most of the heat leaving me comfortable. I rarely have a pocket – as I am now wearing as few clothes as are compatible with the demands of Indian modesty – so I am thinking of putting one in my bag and conducting a test. Thankfully I don’t think it has to be peeled.